Photo from Botswana Predator Conservation Trust

One of the best perks of working for Wild Me is looking at a huge amount of wildlife photos. We work with a lot of different species, and we get to know these animals through the particular lens of researchers’ photography: from the adorably round Saima ringed seals who sunbathe proudly on lakeside rocks, to humpback whales, who are the most glamorous and photogenic cetaceans, presenting their flukes so clearly and often it would make a blue whale blush. A side effect of this view is that we develop a good-natured resentment for some animals that are just hard to parse, whether it’s because of patterning, tight-knit social habits, or both. Perhaps the most egregious example of this is African wild dogs, who are so crafty they forced us to build a new component of our computer vision pipeline.

As our users know, the first step in our image processing is detection, where we extract bounding boxes from images, outlining the animals in a photo and applying species labels to each box. We do this using deep convolutional neural nets trained on each species we detect. In terms of machine learning, this is one of the most high-tech parts of our whole system. The detector can find any number of boxes in one image, which is crucial for social species like zebras, dolphins, and wild dogs where there might be a dozen animals in one picture. It can also label any number of species, a feature that’s especially useful on the incredible photos we see of african megafauna, where zebras, giraffe and more commingle on the same savannah.

Now enter the hounds: African wild dogs are identifiable by their uniquely-mottled coats, so we trained our wild dog detector on the animals’ whole bodies, and we ID these bodies successfully with the HotSpotter pattern matcher. In addition, wild dogs are one of several species where secondary characteristics are helpful for individual ID. There are a few distinct morphs (my personal favorite synonym for a phenotype) we see in the coloration of a dogs’ tail, from as simple as all-black to what researchers call “double black brown”. This led us to train a tail detector and morph labeler, so that every wild dog photo comes back from detection not only telling you where the dogs are, but where the tails are too, and even what morph.

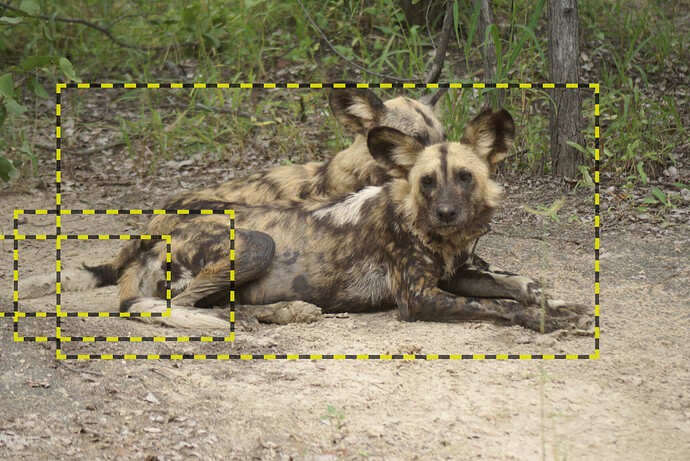

Here’s where things get complicated. Our detector produces a bunch of bounding boxes with any number of labels: zebra, dog, dog tail, dog tail, dog, giraffe for example. Architecturally, these bounding boxes and labels are unaware of each other and exist basically out-of-context. So the problem we’re addressing in this blog post is part-body assignment, or how do we tell which tail belongs to which dog? At first the problem sounds pretty simple, just pin the tail on the closest dog! But look at enough pictures of wild dogs, and you’ll understand pretty quickly why that logic won’t cut it. They are super social animals, almost always photographed in a pack, standing close to each other, twisted in weird shapes, tails and bodies all over the place.

A straightforward example of hard-to-assign tails with bounding boxes from our detector. Photo by Clive Fletcher

We tried at first to assign tails and bodies naively, using some handwritten logic about finding the closest tail to each body and falling back on the researchers’ own decisions when we couldn’t sort them all out. Our users on africancarnivore.wildbook.org reported that this was inconvenient in practice; they spent too much time manually assigning the tails… We decided to address the problem in a robust way with a new machine learning component, knowing that we could later generalize the approach to help other Wildbook users and species who might encounter this assignment problem.

The first thing to do when building a new ML component is to precisely define the problem at hand: what are the inputs and desired outputs of the system? In this case, our inputs are the annotated images–bounding boxes, labels, and so on–that are themselves the output of our detector. And what we want to produce is grouping all of those annotations into bins for each animal in the picture, tails and bodies together.

This framing can help us address the elephant in the room: why don’t we just retrain our detector so that it groups annotations together using those fancy deep convolutional neural networks? Why train a whole separate assigner component instead of upgrading the detection architecture itself to be more context-aware? The short answer is, it’s not that simple. Our detector would need to be redesigned from the ground up with a new, unproven architecture. Computer vision is a huge academic field with thousands of publications a year, and we benefit greatly from using standard problem formulations like “outline and label the things in this picture,” which allow us to use well-studied practices and techniques to get the highest accuracy possible. Changing the problem definition of the detector would simply be too great an undertaking with an uncertain payoff. Instead we will augment it with a subsequent assignment step in the pipeline.

For this new assigner, we want to pair up the annotations that come from our detector, grouping parts and bodies of the same individual. We can make this a little more concrete by defining a metric that we’d like to produce: assigner scores. For any (tail, body) pair in an image, we want to generate a score that represents our confidence that they belong to the same animal. We can then make all the assignments in an image by pairing off all the tails and bodies sorted by those assigner scores. The scores should also have a natural threshold under which we don’t make assignments, because it’s certainly possible that we see some “orphaned” tails or bodies in a picture that don’t belong to a proper tail-body pair. This could happen because a dog is cropped off the side of an image, or partially obscured by flora or one of its packmates.

We’ve now defined the inputs, outputs, and basic workings of the assigner, and are faced with the biggest design question of them all: what type of algorithm should we use? Our computer vision backend already includes a python library called SciKitLearn, an open source package containing dozens of tried-and-true machine learning methods like random forests, decision trees, and nearest-neighbor classifiers. These algorithms are relatively straightforward and lightweight, but they’re still quite powerful and widely-used. Decision trees, for example, are used to identify financial fraud, and nearest neighbors are often employed as recommendation algorithms like for Amazon products or Netflix shows. Further, the SciKitLearn algorithms share a common API, which makes it very easy for a programmer to train and compare different models on the same data. Rather than deciding a priori which algorithm to use for the assigner, we were able to experiment to find what works best for the problem.

If you’ve read our blog post about the PIE algorithm you’re familiar with the concept of features/embeddings, which are numerical representations extracted from images that are designed to help answer a particular question. We analyzed the data to extract the most valuable features we could identify. These features describe each (tail, body) pair in an image, and should contain the relevant information for making assigner scores; they will be the input of the ML model that generates those scores. The features we ultimately deployed are 36-long vectors of numbers, describing traits such as,

- The coordinates of each bounding box in the image

- Viewpoint labels such as Left, Front-Left, or Back

- How much the two boxes overlap

- The area of the tail annot as a fraction of the body annot

- The relative position of the tail to the body

Even though the last three bullets could be derived from the bounding boxes alone, computing them automatically makes the problem easier for machine learning models to incorporate. We chose these features so they’d allow logic like, “if the tail is bigger than the body, they probably don’t go together”, “if the two annotations are far apart, they probably don’t go together,” and “if you’re looking at the right side of a dog, the tail should be on the left side of the image”. Another thing to notice is that these features don’t contain any pixel information, meaning the image itself is not going into the assigner. Parsing the actual colors and shapes of the image would require a more computationally-expensive system like deep learning, and significantly more R&D.

After designing the assigner feature, we computed those features for a large catalog of high-quality wild dog data we’d previously collected. This data had been manually reconciled, with tails and bodies assigned correctly by human reviewers. This was our training data: the inputs (assigner features) and desired outputs (correct tail-body pairs).

We trained a large number of SciKitLearn classifiers on our training data, teaching them to classify a part-body pair as either the same individual or two different individuals. Because we have some fast computers and many of these methods are relatively lightweight, we were able to train a huge number of different algorithms while also comparing a handful of alternate input feature definitions. All in all we trained 98 different models from 16 different types of learning algorithms. For a given type of algorithm, we used another layer of learning called hyperparameter optimization to choose the best settings for that algorithm; so we not only trained each machine learning model, but explored entire classes of models to find the optimal settings for learning the assigner task.

I’d like to spend a little time describing the best-performing assigner model we found through this process, because it’s charmingly simple. After searching through those 98 models and configurations, a humble decision tree was tied for the highest accuracy. A decision tree works exactly like a dichotomous key in biology: the tree is a series of yes/no questions about the input data that get progressively finer-grained until you can confidently make a decision. Training a decision tree is an algorithmic version of making a dichotomous key: the system looks for a variable that divides the training data into two subsets, with the goal of maximizing the internal consistency of each set regarding the target outcome. In other words, our decision tree asks a series of yes/no questions of a given assigner feature, where each question sorts the training data into “same animal”/“different animal” bins as efficiently as possible. We tried other methods that are more advanced applications of the decision tree concept, like random forests (where “forest” means literally a collection of decision trees) and AdaBoost, but found that they didn’t add any predictive ability on our test data.

We packaged up that decision tree, and it’s now live and assigning tails to bodies on africancarnivore.wildbook.org. Overall, it accurately assigns all the tails/bodies in 63.9% of images, and we admit that number was a bit underwhelming at first. However, it has been a huge improvement on the platform, and immediately deleted hundreds of duplicate records that had been made by the old process (if we detect multiple dogs in a single image we create one encounter for each dog, so insufficient assignments results in erroneous encounters). 90% of images have zero or only-one assignment errors, which can quickly be fixed by the researcher when they’re noticed. And after testing the improved system, user told us over email “I think you folks are bloody miracle workers!!!” Even so, we can’t help but think how this could be improved. Having tested so many different “naive” classifiers and input features on the assignment problem, we’re fairly convinced that this is the performance ceiling of this type of approach on this data. So if we need stronger assigners in the future, we must extract semantic information from the pixels, shapes, and colors in these photos, and for that we’ll need something more powerful than decision trees, such as deep learning.

How many dogs even are there? Photo from Botswana Predator Conservation Trust

On a closing note, I’ll return to the inveterate rascality of these dogs. After integrating the wild dog assigner, I trained another assigner model for sea turtle heads and bodies. We detect those features separately on the Internet of Turtles, and for users taking photos at nesting sites, we need to make sure the turtle heads and bodies are assigned correctly. That model was 90% accurate, a much higher score than we reached on the dogs! From our point of view, sea turtles are a more cooperative species.